HIDENORI ISHII

YUME NO SHIMA (DREAM ISLAND)

Hidenori Ishii, born 1978 in Yonezawa, Japan, is a Queens-based artist whose work approaches the environmental landscape, especially post-atomic radioactive ecosystems, through a fusion of art historical connections, personal narratives, and socio-political subject matter.

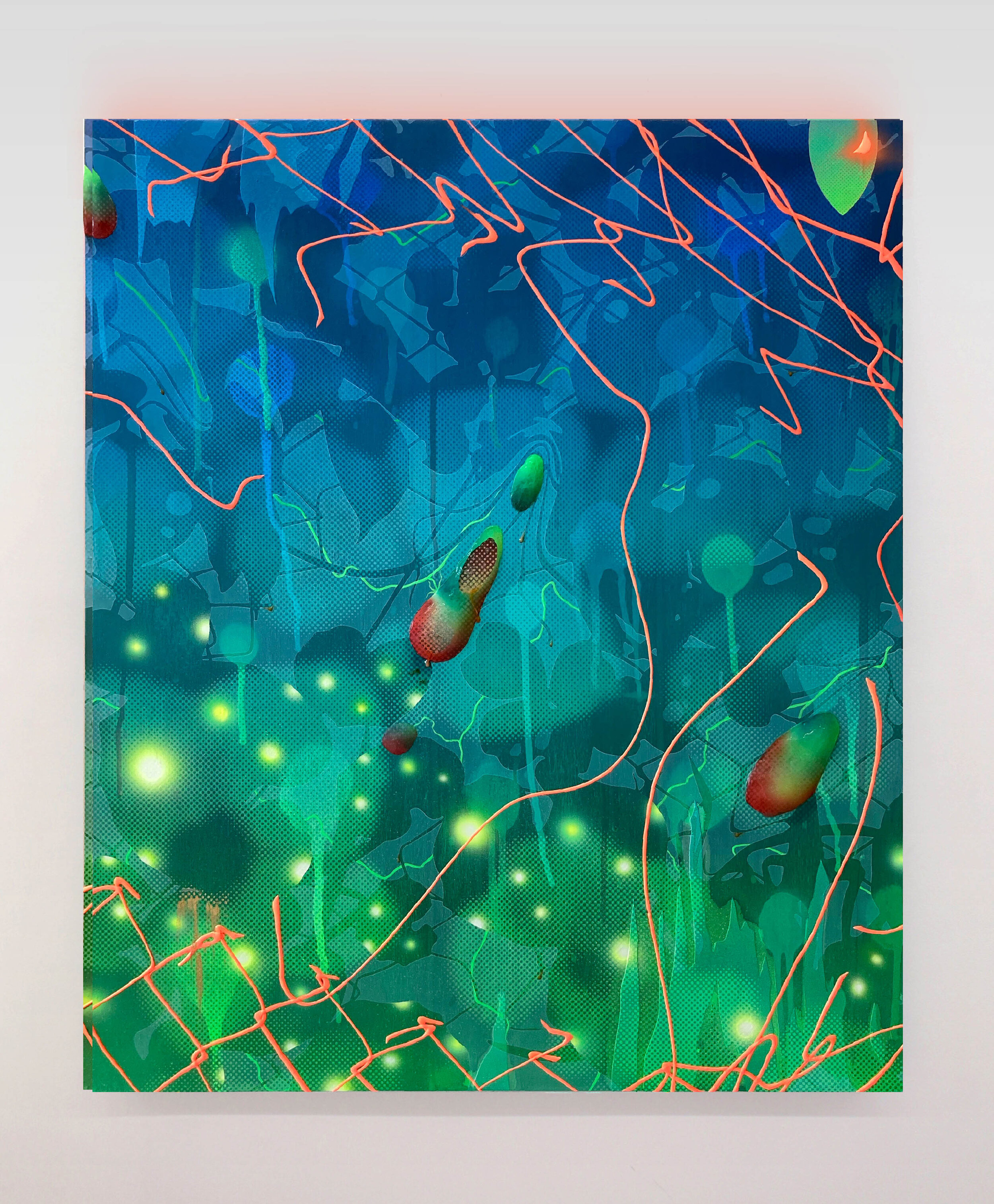

Ishii, who spent his childhood playing in the area near Fukushima, has been using his floral pattern since Grow Till Tall (2013) and The Remains of the Day series (begun in 2013) which directly responded to the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant meltdown. Also, with signature use of synthetic resin Kuricoat — the green tinted version of the polymer sprayed at the Fukushima Daiichi site in an attempt to prevent dispersion of contamination — the artist constantly explores the subject of reflection and invisibility. Representative works such as the MIRЯOR series stage the fear of invisible radiation and the emotion itself through the transparent surface. In the contrast between organic imagery and artificial material, Ishii envisages a future after environmental and societal trauma. He reveals a hopeful environment where humans and nature coexist and sustain one another.

Fukushima Daiichi site post meltdown. Kuricoat, the green tinted version, sprayed at the site in attempt to prevent dispersion of contamination.

The special edition series of screenprints secured between layers of plexiglass is a stretch of Ishii‘s art practice and addresses the mood under the looming pandemic. He agitates the dichotomy between concepts of invisibility and reflection as well as separation and protection. It acts as a mark of the tense moment and makes the invisible emotions visible. More importantly, as his practice is tied to how nature survives the tragic incident created by human activity and error, and then revives, the new edition indicates hope after the bio-disaster and the social, political environment shifts. Although the profoundly challenging events of 2020 may have longer and deeper influence than one could imagine, just like the Fukushima nuclear meltdown, the brightness in humanity will still prevail, as the flowers.

ÍS MIRЯOR - Pink Fluorite, 2020, 2 layers of screenprint on paper and plexiglass, 18 x 16 x 4 inches, edition of 3 with 1 AP. Additional iterations: ÍS MIRЯOR - Yellow Fluorite; and, ÍS MIRЯOR - Green Fluorite.

The Remains of the Day II, 2013, 39 x 39 inches, acrylic and Kuricoat C-720 (synthetic resin) on panel ; MIRЯOR (Pink), 2018, 16 x 12 inches, acrylic and Kuricoat C-720 (synthetic resin) on aluminum panel

Grow Till Tall, 2013, 80 x 112 inches, acrylic and Kuricoat C-720 on Panel

Townsend extends special thanks to Minwen Wang for her contributions to Yume no Shima (Dream Island). Images throughout courtesy of the artist and Erin Clulely Gallery.

IN THE STUDIO WITH HIDENORI ISHII

Japanese artist Hidenori Ishii (b. 1978, lives and works in New York) welcomes us into his new space in Long Island City and describes how nuclear and radiation research has molded his art practice.

by Myriam Erdely, September 2020, MyriamErderly.com FST StudioProjects Fund

Thank you for inviting me into your new space! Last year, you won a grant from the FST StudioProjects Fund, which was created by Frederieke Sanders Taylor in order to help artists defray the cost of their studios in New York City. How has the FST StudioProjects Fund grant changed your practice?

Thanks to the Fund, I took advantage of the opportunity and finally made up my mind to move to a bigger space in March as the scale of my work increased and I had started outgrowing my old studio space in which I had spent 8 years. And now I have windows for the first time in NY (this is my fourth studio) and the light from the windows definitely changed the way I see my work.

What are some of the details you noticed right away due to this new natural lighting?

Some painters do not like inconsistent lighting due to several reasons; but I think my paintings are strong enough to shine through really awful color temperature or too much dimness. And with these new large windows in the new space, it’s just refreshing to see how the paintings look at different times of day. Also, I have some works with colored plexiglass and it’s so interesting to see how they interact with the natural lighting in the space.

Tangent I, 2014, 28 x 28 inches, acrylic and Kuricoat C-720 (synthetic resin) on panel

That’s wonderful. Your work has a very great presence, especially in person, a presence in which one can almost fall into. The lighting here is beautiful. Have you been able to work in your new space with the current social distancing Covid-19 regulations? How has the pandemic affected your routine?

The statewide shelter-in-place happened right around the time of the move and after moving things in, I was not able to go back to set up the new studio space for a long time. Which was a bit frustrating at the beginning, but I slowly started going back in there to restart in a way. Seeing no one in the streets and in the studio building; where usually many design and production firms were active, was quite a surreal feeling if I recall. Following the stories on the radio or YouTube while working there; it felt like a complete isolation both physically and emotionally.

At first glance, your work is very bright and colorful, but at a deeper level there seems to be an underlying darkness that lingers underneath layers of patterns and imagery, can you tell me a bit more about the issues you are trying to uncover?

I actually didn’t think of or realized this until recently, but my work has very much been affected by and is somewhat of a response to current events. I mean, when I look back at my work from my grad school years at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, they were also, but somehow it just got clearer during this pandemic - maybe I had enough time to look back or it happened while re-organizing my stuff in the new space. I came to the United States in 1997 to study environmental science but ended up studying art at the College of Visual and Performing Arts George Mason University in Virginia, and learning the Western history of art. My interest in the field of science has always been apparent in my work throughout the years. For instance, I’ve been working on this ongoing series called IcePlants, which is based on my observation, response and projection of the 2011 nuclear spill in Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plants. And I’ve been expanding my research beyond this specific location and visiting actual sites to witness the transformation first-hand; in 2016, on the 30th anniversary of the Chernobyl disaster, I visited the Chernobyl exclusion zone which is where the nuclear accident happened.

FTM (FOLLOW the MAP) F & N, 2015-17, 16 x 15 x 35 inches, acrylic, Kuricoat C-720 (synthetic resin) on cast urethane, memory foam, acrylic panel, copper - a set of two

That visit must have been an incredible experience. Can you speak more about what you witnessed and how has your work aesthetic changed from seeing the site?

I remember some of my friends were telling me to watch HBO’s Chernobyl miniseries at some point, and several months later, I finally watched all 5 episodes at once on a 12-hour flight to Japan! I recognized some scenes and objects from the pictures I took during my trip. Observing the abandoned buildings and the powerful presence of nature in the evacuated zone was an incredible and surreal experience. One of highlights of the trip was seeing the actual remote-controlled robots/vehicles on display on the way to the Chernobyl site, which appear in the show as well. These robots are designed to withstand the super high radiation zone where humans cannot tolerate, although many did not and have “died” near the reactor’s core. It was striking to be reminded that even those inorganic machines could also not last and I had strange feelings while seeing those corpses after 30 years and freshly re-painted in bright colors!

This reminds me, there is a wonderful series that you made called FTM (FOLLOW the MAP) where small colorful oval paintings are each laid into their own translucent plexisglass container; there seems to be a desire to display, to present, but also to contain... much like the way the Chernobyl nuclear reactor is concealed under a structural dome, and yet it remains a popular tourist attraction.

That’s an interesting observation and I like that! The Follow The Map series actually started in 2015 before my visit to Chernobyl. Unlike my other monumental landscape works, the Follow The Map series consists of small pieces that could almost be carried far away, like how some plants’ seeds get blown away by the wind and later find a new home and habitat. Most of my work seem to have shared genes/memories. Originally, I was hanging these pieces on the wall. But then post Chernobyl trip, I started thinking about the fate of living organism vs. the life of inorganic compounds. Through my research I discovered that some human organs are now being 3D-printed and technology could possibly substitute our body as a container as long as the brain cells are functioning in the near future. That’s how I got the series into a more sculptural form and was interested in displaying the small breast-shaped cast resin paintings within a neon plexiglass container, surrounded by memory foam and upheld on the wall by a copper pipe system. They look like they could be lab samples ready to be tested or artificial body parts for sale. These small, gene-like works might be scattered like seeds, germinating hybrids between the biological and artificial, between the natural and technological.

Nostalgia VI (green/pruple), 2016, 60 x 48 inches, acrylic, Kuricoat C-720 (synthetic resin), metallic on panel

Flowers are a recurring motif that repeatedly appear in your paintings, how did you first come across this imagery? How have you appropriated it, and can you speak more on your process of repetition.

So, flowers first appeared in the IcePlants series I made in 2011-12. Obviously, one can easily make an association with Andy Warhol’s 1964 series Flowers; and also see that I am exploring the idea of manufactured images. Back in 2011, I was working as a textile/print designer for a large fashion retailer and it occurred to me one day to introduce into my own paintings a floral pattern that has an infinite repetition, as opposed to Warhol’s single set of four flowers. This is how I started depicting my signature floral pattern that acts almost like a background, or the air or the surrounding space. I wanted to create something translucent. By starting with a grayscale printed floral pattern, on which I spray-painted thin transparent layers of colors, blues, greens, pinks, at a very thin opacity mist, I was combining multiple layers of paint and created more contrasts within the spectrum. In this series, I also used silk-screen and ran with the idea of repetitive patterns in halftones. And as a silk-screen medium, I used a synthetic resin called Kuricoat C-720.

MIRЯOR - Fluorite, 2019, 48 inch diameter, acrylic and Kuricoat C-720 (synthetic resin) on panel

Yes! I had noticed that most of your paintings and sculptures are made using Kuricoat, can you tell me more about this medium and if this natural/synthetic dichotomy of wanting to explore natural formations using synthetic materials is a conscious choice.

Certainly. Kuricoat C-720 is a green synthetic water-based resin that was actually used at the Fukushima Daiichi site in order to seal the radiation into the ground right after the meltdown. My process of repeating the floral pattern as a recurring background is very synthetic/artificial and yet the image of the flowers remains an "organic/natural image” when the paintings are completed. It is tied to how nature/flowers come back on their own in their actual natural state despite a tragic incident created by human activity and error. It suggests the invisible manufactured threat of radiation in the air. The spill of radiation from nuclear plants contaminate the surrounding areas and keep multiplying. And yet nature prevails, every time.

Nature seems to be an integral theme for you. Did you grow up close to nature in some way?

I grew up in a small city called Yonezawa in the north of Japan where I have so many great memories of interacting with nature, insects and so on. But at the same time, I somehow had a fascination with a particular landfill, Yume-No-Shima (Dreamland in Japanese), located at Tokyo-Bay. It was a vast island reclaimed by industrial and households’ wastes and toxins which was a huge environmental issue in Japan in the 60's and 70’s. However, over the decades, the land has been properly processed and intoxicated, and today a green landscape has developed. After so many years, the land has transformed into a park and a communal space for people in Tokyo. This whole experience of transformation interests me very much. And, in many ways, I believe in nature/botany over human activity.

On the Fence, 2019, 60 x 288 inches, acrylic, Kuricoat C-720 (synthetic resin), powder pigment on panel, fluorescent light fixtures, steel posts

A great majority of your work is steeped into the painting tradition; however, you often divert into sculptural explorations. In your latest show titled “On the Fence” at the Erin Cluley Gallery in Dallas, TX, there are a lot of subtle interventions surrounding the paintings; fluorescent lights on the floor, yellow steel posts, green-colored electrical wires, flower shaped screws... What is the significance of these sculptural elements?

Creating an environment and suggesting a tie between what’s painted on the canvas and the actual space in which the painting occupies seems natural and crucial for some of my work. I’m interested in more than just the pictorial sense of my paintings. To go back to the Follow The Map series I mentioned earlier, elements like plexiglass, memory foam and copper pipes are the support system of the paintings. Each material is functional yet put together they are nonfunctional and create the metaphorical environment the paintings fit in. They become like a bridge between the metaphysics of the painting and the reality of the surrounding space. In my show “On the Fence” at Erin Cluley, the fluorescent lights suggest the growth of plants in LED environments and the presence of electricity through green electrical wires signifies the flow of energy. The flower head screws seem to be the result from the drill holes where pollen-like yellow powder pigments is mounted around the hole. Metaphorically, these elements imply the living and transformation of the environment.

On the Fence (detail), 2019, acrylic, Kuricoat C-720 (synthetic resin), powder pigment, copper pipe, cast urethane, steel posts, glass vase, red wine

As I walk around your new space, I can’t help but to notice the newer works you have hanging. What about this new Pop element, is it from a grocery store flyer?

In fact, I am using an image transfer of a vinyl advertisement, of vegetables and fruits from a supermarket, which I have shrunk into a smaller size to fit. I’ve actually been collecting these for a long time, because I find these types of images funny, in a generic kind of way. And at the same time, they are super blown up so that one might not even recognize them as being vegetables, there’s an abstract element to them. When the pandemic happened, I found myself thinking of the role of the supermarket in our lives. We never thought about our access to the market before in such an intense way. It is such a lifeline. And during these difficult times, going to the supermarket became the only social life we had in a way.

On the Fence - Still Life V, 2020, 24 x20 inches, acrylic, Kuricoat C-720 (synthetic resin), copper, powder pigment on panel

And what are these relief red shapes?

They are tomatoes. I use this very thick glossy transparent medium to shape distorted tomatoes which takes about two weeks to completely dry. I refer to them as tomato slices since I use a blade knife, to cut them and slice them, to create the relief. These newer works are kind of a departure, or I’d say a connecting flight from my IcePlants series; I have been concerned about the genome. There is a facility in Ibaraki, Japan, where an experimental vegetable field is intentionally radiated. The resulting growing plants mutate and create a new sort of crop. The tomato is well known for that type of radiation experiment, as being the pioneer for genome edited foods. Surprisingly, it is out in the markets and is not considered a GMO food (genetically modified food), according to the FDA. This goes hand in hand with my fascination and research on radiation and nuclear spills.

I love how you are talking about these issues that are very concerning, such as how we are consuming genome edited foods that could have devastating effects on us, but you are creating these inviting, colorful, beautiful oozing green landscapes, or environments for these really dark subject matters. It’s like you’re making nuclear waste... enticing!

That’s the world we live in right now. People probably don’t question enough...

FTM (40.749711, -73.943608) - Green Bill Board, 2020, 14 x14 inches, screenprint on fiber paper mounted on panel, collected acrylic sheet & cast urethane

Congratulations on your recent Lower East Side Printshop residency. How has this opportunity influenced your current practice so far, have you worked with different or limiting parameters?

Thank you! It’s a strange time to be in the program under the influence of the pandemic, but I’m enjoying the accessibility to the new medium. I mean, I’ve been screen-printing for a long time but I am now examining the idea of printing and deciding between different papers/supports/ processes that are completely new to me.

What are you working on now?

Actually, I am currently working on a new series called FTM - Green Bill Board which questions the social and economic impact of the ongoing invisible fear and influence of the pandemic in the New York City cityscape. The work consists of several stages; first, I screen-print a see-through image with gold paint on a 12 x 12 inch diamond-shaped plexiglass. Second, I go out into the streets, specifically near construction sites and try to find a diamond-shaped window, the kind you can look through, and I take out that window and replace it with my work. I keep the graffitied/damaged plexiglass window and use it to create a new work. I’m very interested in the exchange aspect. When I began to think about printmaking, somehow, cash bills first came into my head, how money is printed. In these newer works, I take the damaged plexiglass construction window, and screen-print an abstracted image. I focus on a tiny part of a cash bill, that I blow up to a microscopic view of 1/2073 scale. It’s amazing to see all these details that exist on the printed bills, like an olive plant, a flag, I’m zooming in and printing out these details.

Do you think these new-found currency patterns are going to make their way into your painting practice?

I’m not sure... quite possibly! I somehow always find myself gravitating towards new patterns.

ON THE FENCE — THE MAKING

Townsend extends special thanks to Myriam Erdely and Minwen Wang for their contributions to Yume no Shima (Dream Island). Images throughout courtesy of the artist and Erin Clulely Gallery.