COLETTE ROBBINS

○

TEMPUS

○

COLETTE ROBBINS ○ TEMPUS ○

TEMPUS

Text by Tess Hallman

The past, the present, and the future: markers which comprise the very fabric of time and place that drive narratives of humanity and history. Over several millennia they have manifested in unique ways across cultural landscapes impacting not only each society, but also the larger narrative of the human experience. Their representation comes in many forms. In ancient Rome the god Janus was keeper of the door, and ultimately the portals that ushered one through the beginning and end of life experiences. For Roman society he maintained a reassuring presence through any transition made between the three markers of time; he balanced the duality of ushering out the past and embracing the future all while managing the never ending liminality of the present moment. This mythology radiates through the Western canon in various renditions which all clearly call back to Janus as a foundational figure in historical analysis.

As history progressed one can see shift from religious justifications to a development of a scientifically based quest for knowledge and universal truth. As indicated by European philosophers such as Foucault and Freud, a push toward regulating scientific logic and making new discoveries was championed in the social landscape of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The classical episteme they developed and operated in called for an encyclopedic manner of categorizing all aspects of humanity but their work manifested most obviously in the private collecting practices of art and cultural artifacts. Here one can see a movement motivated by a desire to examine the practices of the past and find new methods of revolutionizing the future, however there was a gap in the motivations of science that needed to be addressed, the present. In a time where innovation was prioritized the Western world was changing at a rate that often outpaced the ontological changes of the public sphere. Born out of this liminality was Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, a novel that remains relevant as a means of grounding ones sensibilities about the potentials of scientific progress and the human condition within the lessons from lived experienced form the past.

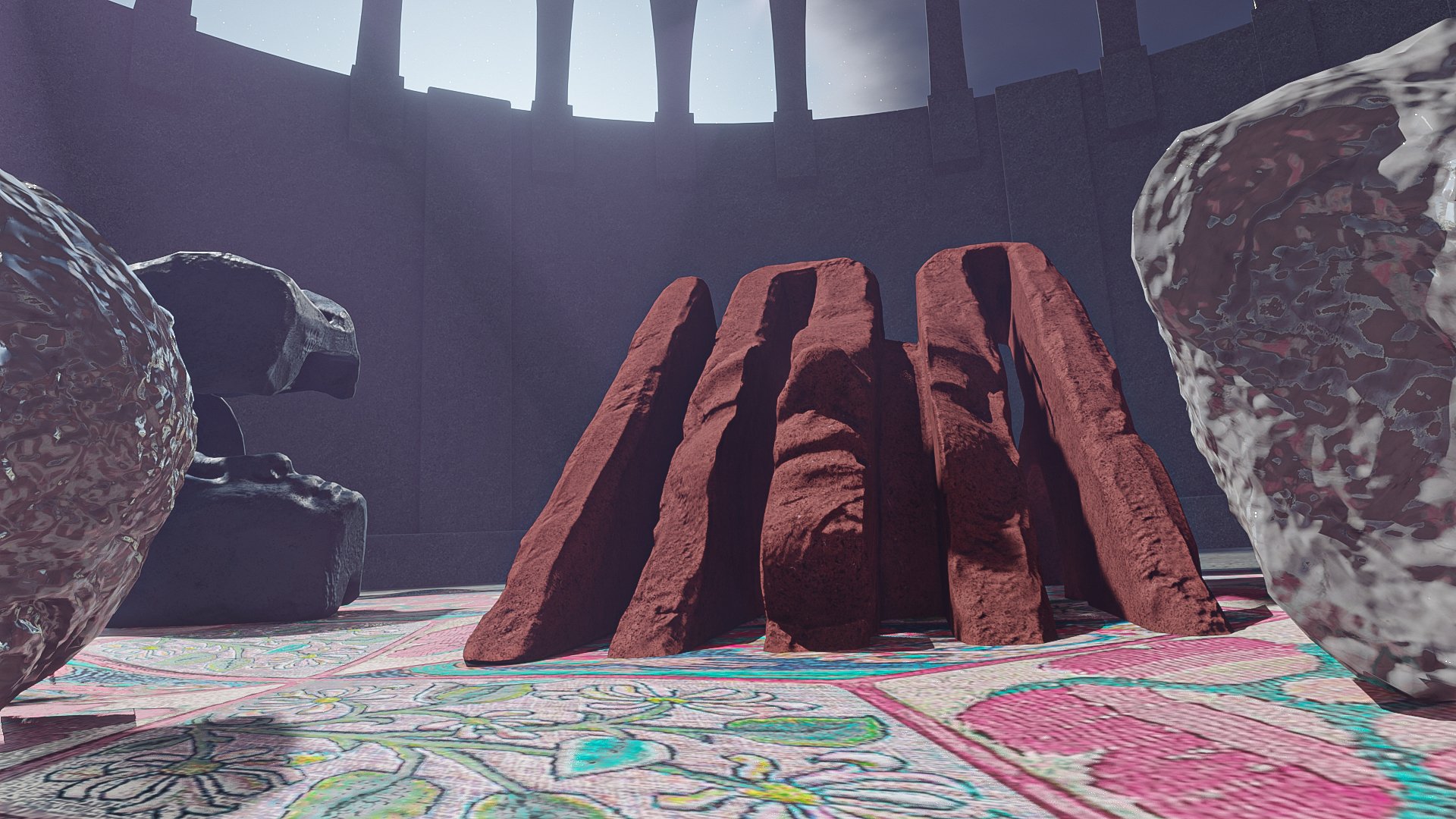

Installation view of Dimensional Jump, an imagined exhibition space built in 3D. From left: Spirit Guide, 2022; Sticks and Stones, 2022; and, Home is the Edge of the World, 2022.

Both Janus and Frankenstein are historical pin points through which one can reflect upon the continuously evolving nature of the human experience. They are tools that speak to the processes of living in a never ending cycle of archetypes that can be identified throughout human civilization; but further, they are two elements artist Colette Robbins calls upon in her body of work. As a hybrid digital-analog sculptor Robbins takes inspiration from these key pieces of the Western canon, the one that has informed her experiences, and evokes complex conversations around topics of technology, mythology and interconnectivity. Her style takes inspiration from ancient symbols, archaic armor, and augmented Greco-Roman heads, which allow her to imprint her own identity into the piece as she works with her unlimited imagination.

As an artist who has positioned herself at the leading edge of the traditionally male dominated field of Tech, Colette Robbins actively works within crypto communities to craft digital animations and sculptures that sell as NFTs on the blockchain in addition to her traditional sculpting practices. Through this work she finds herself assessing the themes of Shelley’s literature and engaging with areas of life traditionally guarded by Janus. Thus, she becomes a modern evocation of these practices that one can locate time and time again in Western history. She lies at the center of this generation’s intersection with technological advancement, yet uses elements from the past to ground her own experiences and address them in a way that speaks to the reality of our daily experiences. To truly understand the collection of Colette Robbins one must first dive into the historical and generational themes of time championed by Janus and the complexities of transhumanism explored in the work of Mary Shelley (the latter two topics to be explored in a second installment of Tempus).

Colette Robbins, Home is the Edge of the World, 2022, 3D animation, 23 seconds.

JANUS

Roman marble bust of Janus. Musei Vaticani - Museo Chiaramonti. Image by Marie-Lan Nguyen.

Ancient Greece and Rome are universally recognized as the beginning of the Western canon of knowledge. Much of the world we live in today is rooted in major ontologies first manifested in these societies; therefore addressing the god Janus is central to understanding the intricate sentiments that underlie Colette Robbins' work.

The history of this deity begins before Rome was even established, in what is now described by scholars as ancient Italy.1 In these societies numina were vague spirit like essences attached to certain objects, and while everything had a numina only a few became legends as socio-cultural practices mutated over time.2 Janus is perhaps the most important of all of them. His origin story, and reasons for identifying as a male figure, are deeply connected to his central symbolism of the doorway or door frame more specifically. In these cultures, the entryway to the home was understood as a man’s domain for domestic care because it “was a strategic point since it was the place at which attacks from foes were most expected”.3 As men were largely responsible for the activities outside the home, they were also responsible to protect the structure and its inhabitants from the threats that lurked in their exterior territory. This leads to Janus’s deep interconnectivity with the concept of masculinity and the idea that he is a protective spirit that he is a protector, a sentiment that radiates through his legacy.

Colette Robbins, Spirit Guide, 2022, 3D animation with audio, 30 second loop. Music: Ravaged Hearts, Royal Robbins.

Along with his status of protector concerning the doorway, this association imbued Janus with another very important set of meanings. Just as he was understood in a role to protect the people on the inside from the uncertainties of what was outside, he became a Roman symbol for duality. The doorframe of a home is a liminal space between nature and the home, but he quickly became a guiding force for many scenarios. For example, he was the celestial entity that oversaw the interactions between inside and outside, past and present, young and old. Because of his ambiguity, he was often called to the two-faced god. There are only a handful of depictions of Janus but they all show him in the same manner where “one of these faces is that of a youth who was symbolic of beginnings and the other is of an old man emblematic of the end of things”.4

This same sentiment was also conveyed through another set of semiology, where a key became his universal identifier. The key is inherently tied to the doorway but it also alludes to the idea that Janus has access to information that may be withheld from his devotees. In mythology, he was understood to have unfiltered perceptions of past realities, as well as access to the unknown occurrences of the future. His importance becomes undeniable when one examines Janus’s ritualistic presence in the proto-Roman and Roman religions.

Janus was a major player in all religious and spiritual ceremonies for both cultures. He was primarily invoked during practices such as birthing ceremonies and end-of-life rituals, simply because these are the events that delineate a person’s lifecycle. In these crucial moments, Janus can see what is to come for a child and offer reflection, as well as assurance, for those who are dying. He became the god of generations as he was increasingly connected with this particular aspect of duality. However, scholars are vocal about the fact that “to him, the Romans ascribed all things, the ups and downs of fortune, and civilization of the human race by agriculture, industry, art, and religion”.5 This was exemplified in two major ways, both of which are outlines in Ovid’s surviving piece of ancient literature Fasti. The first is that he was always the initial name stated in any Roman prayer invocation, regardless of the occasion or who the primary deity of worship was.6 The second shows how this place of importance followed suit even into the secular aspects of life, for when examining the Roman calendar one can see that “the month of Janus comes first because the door comes first”.7 This still holds today, for the root of the word January in today’s systems of time management were developed in languages derived from Latin.

Installation view of Dimensional Jump, an imagined exhibition built in 3D. From left: Home is the Edge of the World, 2022; Relic of Personifier; Personifier, 2022; and, Sticks and Stones, 2022.

This overarching association with duality and guidance is still at work in the cultural codex today, even beyond the calendar, and it is what Colette Robbins finds intriguing about Janus’s functionality as a deity. In her artwork, she uses Janus as an inspirational tool through which she explores the well-known cultural tropes that people are frightened of what is to come and look to the past for guidance. It is fact that the Western canon of human history is built upon cultural systems that are complexly layered with ideologies from its Eurocentric past that once provided a sense of security during times of, sometimes intense, scientific and social progress.

Janus is a perfect representation of this cycle for his earliest lore began in ancient Italy, then was carried into traditions of the Romans. However, the influence of the Pantheon he once presided over was present in cultures far beyond this geographic and historical moment as a result of this cyclical phenomenon of human nature. Some of Colette Robbins art traces this idea directly into the Vendel period, which thrived well into the 11th century.8 According to ethnographic scholar Judith Jesch, the practices of boat grave burials and the ritual acts performed to display a Vendel woman’s kinship group can be linked back to Roman mythology. She displays this connection through an analysis of jewelry worn by the deceased explaining:

“The boat graves, as well as the occurrence of huge button-on-bow brooches with garnets, too large to be worn by a normal woman, but otherwise corresponding to normal button-on-bow brooches are, according to my investigations, symbols of Freyia (Arrhenius 1997). These symbols can also be traced back to a late Roman cult of the goddess Isis where sacrifices of loaded boats as well as garnet jewelry are important items in the cult (cf. Arrhenius 1997& 2001b).”9

This example, although not directly related to Janus himself speaks to one of Colette Robbins' overarching themes as an artist. She strives to have viewers question the often unchallenged system of constructing social dialogues by pulling from and building upon one another. The ability to establish a historical link to Rome is important in this process, for it is the culture widely understood as the foundational moment in Western history. By highlighting the interconnectivity of historical constructions around cultural practices, Robbins draws attention to the reality that recurrent western narratives deeply impact how global systems of defining and redefining socio-cultural rhetoric operate. She calls upon the symbolism of Janus for his inherent ability to reflect on the past, exist in the present, and offer insights into the future, as she is trying to do the same in her work.

While Janus’s presence in various social spheres seems primordial after an in-depth analysis of the way his associated tropes manifest generationally there is a major flaw in his representation; a flaw that also makes him the perfect historical tool to define Colette Robbins’ present-day social commentary. It is important to note that Janus’s roots are so intertwined with the growth and development of Rome that there is no Greek equivalent, which supports the theories of generational development that Robbins engages in her other expression of this deity in her work. This idea is significant because many of Western society’s cultural practices and ontologies are widely understood to trace back to the collective time of antiquity. The two cultures of Greece and Rome are often joined together in public discussion. We see this exemplified in cultural institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which has a singular Greek and Roman Art department.10 As a result one often thinks of them as interconnected and parallel however, Janus acts as a prime example through which one can explore the uncommon belief that most stories have no definitive truth. They are always changing and growing.

This fact may seem simple, yet it speaks to a theory that is essential in the works of Robbins. Janus represents the past, present, and future. He provides a framework through which one can understand how societies approach change and uncertainty by cycling back to past sentiments of social familiarity. Yet, he is also a historical point that narrows down a diverse set of cultural dynamics that preceded his symbolism. By nature, the popularization of Janus as a symbol of masculinity and duality overtime preserved the traditions of Romans throughout centuries yet it also allowed history to lose the culturally diverse voices of those where were overshadowed by the popularized history of the Roman Empire. This speaks to another main motivator behind much of Colette Robbins' works, as she poses questions about the perception of truth. She highlights that history is written by the victors and in the process society as a whole loses an understanding of historic diversity. This becomes problematic as these narratives are immortalized as universal truths in the western canon that fuels the development of society as it progresses forward in time even in today’s global society. In a way, Colette Robbins uses Janus’ connection to duality as a means to highlight the duality of perceived historical fact.

HOME IS THE EDGE OF THE WORLD • RENDERS

SPIRIT GUIDE • RENDERS

FOOTNOTES

1 Mac Mahon, Ardle. "The realm of Janus: doorways in the Roman world." In TRAC 2002: Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference, (pp. 16. 2002): 58.

2 Burchett, Bessie Rebecca. Janus in Roman Life and Cult: A Study in Roman Religions... (George Banta Publishing Company, 1918): 4.

3 Burchett, Bessie Rebecca. Ibid. (George Banta Publishing Company, 1918): 5.

4 Mac Mahon, Ardle. "The realm of Janus: doorways in the Roman world." In TRAC 2002: Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference, (pp. 16. 2002): 58.

5 Mac Mahon, Ardle. Ibid. (pp. 16. 2002): 58.

6 Burchett, Bessie Rebecca. Janus in Roman Life and Cult: A Study in Roman Religions... (George Banta Publishing Company, 1918): 4.

7 Mac Mahon, Ardle. "The realm of Janus: doorways in the Roman world." In TRAC 2002: Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference, (pp. 16. 2002): 59.

8 Jesch, Judith, ed. The Scandinavians from the Vendel Period to the Tenth Century: An Ethnographic Perspective. Vol. 5. (Boydell Press, 2012): 46.

9 Jesch, Judith, ed. Ibid. (Boydell Press, 2012): 46.

10 “Greek and Roman Art .” the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metmuseum.org, n.d. https://www.metmuseum.org/ about-the-met/collection-areas/greek-and-roman-art.

COLETTE ROBBINS •TEMPUS• CATALOGUE OF IMAGES

Installation view of Dimensional Jump, an imagined exhibition built in 3D. From left: Spirit Guide, 2022; Sticks and Stones, 2022; and, Home is the Edge of the World, 2022.

Installation view. From left: Relic of Personifier, 2022; Spirit Guide, 2022; and, The Artist, 2020.

Spirit Guide, 2022, render from 3D animation

Spirit Guide, 2022, render from 3D animation

Spirit Guide, 2022, render from 3D animation

Home is the Edge of the World, 2022, 3D render

Home is the Edge of the World, 2022, Render from 3D animation

Detail: Home is the Edge of the World, 2022

Installation view of Dimensional Jump, an imagined exhibition built in 3D: Home is the Edge of the World, 2022, 3D Animation

Installation view of Dimensional Jump, an imagined exhibition built in 3D. From left: Home is the Edge of the World, 2022; Relic of Personifier, 2022; Sticks and Stones, 2022; and, Personifier, 2022.

Installation view of Dimensional Jump, an imagined exhibition built in 3D. From left: Home is the Edge of the World, 2022; Relic of Personifier, 2022; Personifier, 2022; and, Sticks and Stones, 2022.

Sticks and Stones, 2022, 3D render

Personifier, 2022, PLA (polylactic acid), metal, acrylic, 48 x 18 x 21 inches

Alternate view: Personifier, 2022

Relic of Personifier, 2022, PLA (polylactic acid), metal, acrylic

BIOGRAPHIES

Colette Robbins, born 1980 in St. Louis, Missouri, received her MFA in Fine Art at Parsons the New School for Design, New York, New York; and, her BFA at he Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore, Maryland. Robbins has exhibited her work domestically and internationally including at 101/Exhibit, Los Angeles; P.P.O.W. New York; Deitch Projects, New York; The Hole Gallery, New York; Koki Fine Arts, Tokyo, Japan; and, Workshop Gallery, Venice, Italy. Robbins lives and works in Queens, New York, and is an adjunct professor at the New York Academy of Art, Manhattan, and Pratt Institute, Brooklyn.

Tess Hallman is a New York-based freelance museum professional. She received her MA in Museum Studies from New York University, and her BA (Cum Laude) in Anthropology from Susquehanna University, Selinsgrove, PA. Hallman has worked at Betty Cunningham Gallery, New York, and was previously an intern at Onishi Gallery, New York.