PARINOT KUNAKORNWONG

BOYSHOW

In BOYSHOW Parinot Kunakornwong probes questions of perception, categorization, and history through intimate engagements between his body and artefacts, materials and language which mediate its depiction in both the gallery space and the world at large. Through personal engagements with hegemonic taxonomies of racialised bodies, as well the conditioning capacities of Thai propaganda, Catholic Imagery, and Western Pop culture, BOYSHOW lays out an assortment of objects and imageries whereby historical dynamics find themselves embedded in the vulnerabilities of the everyday.

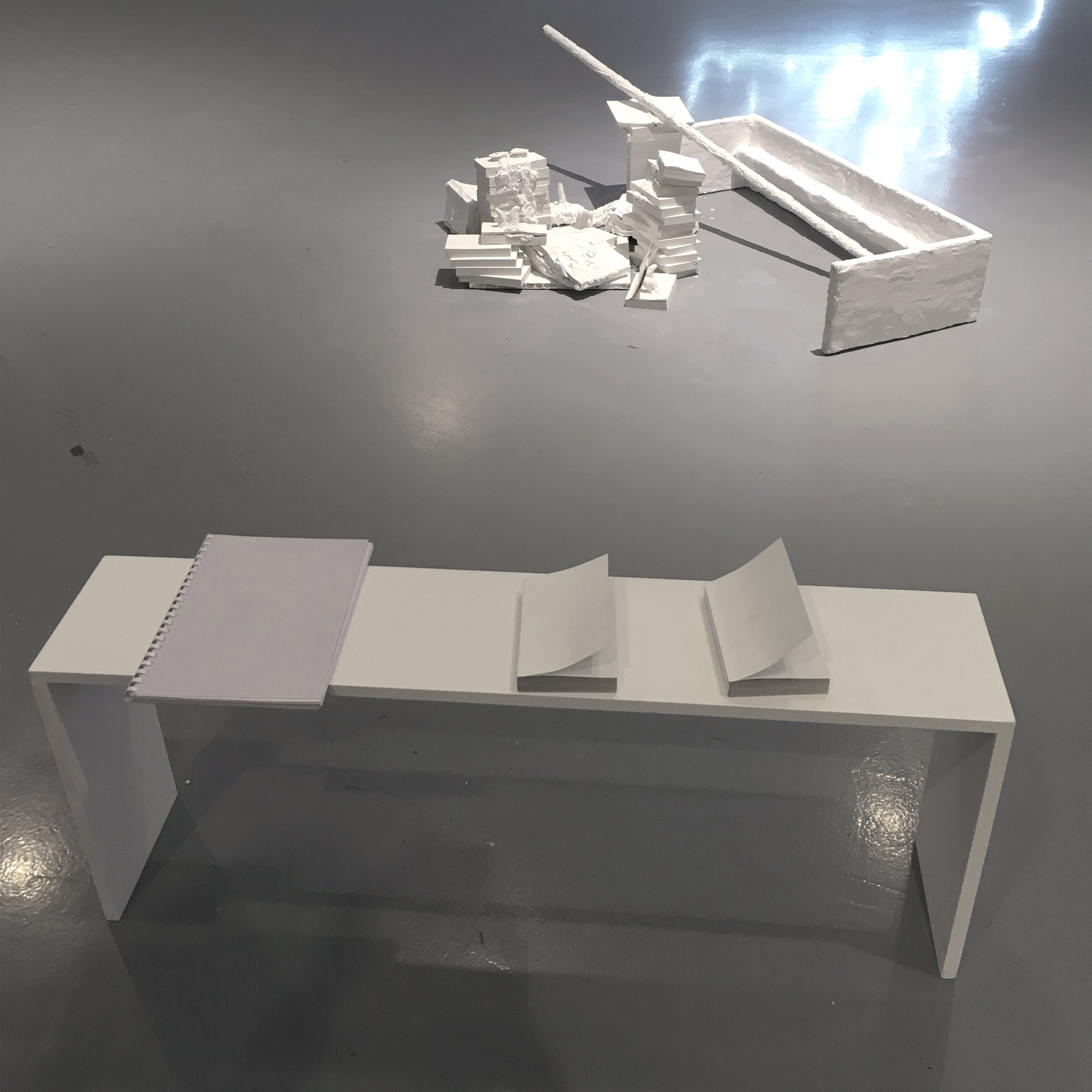

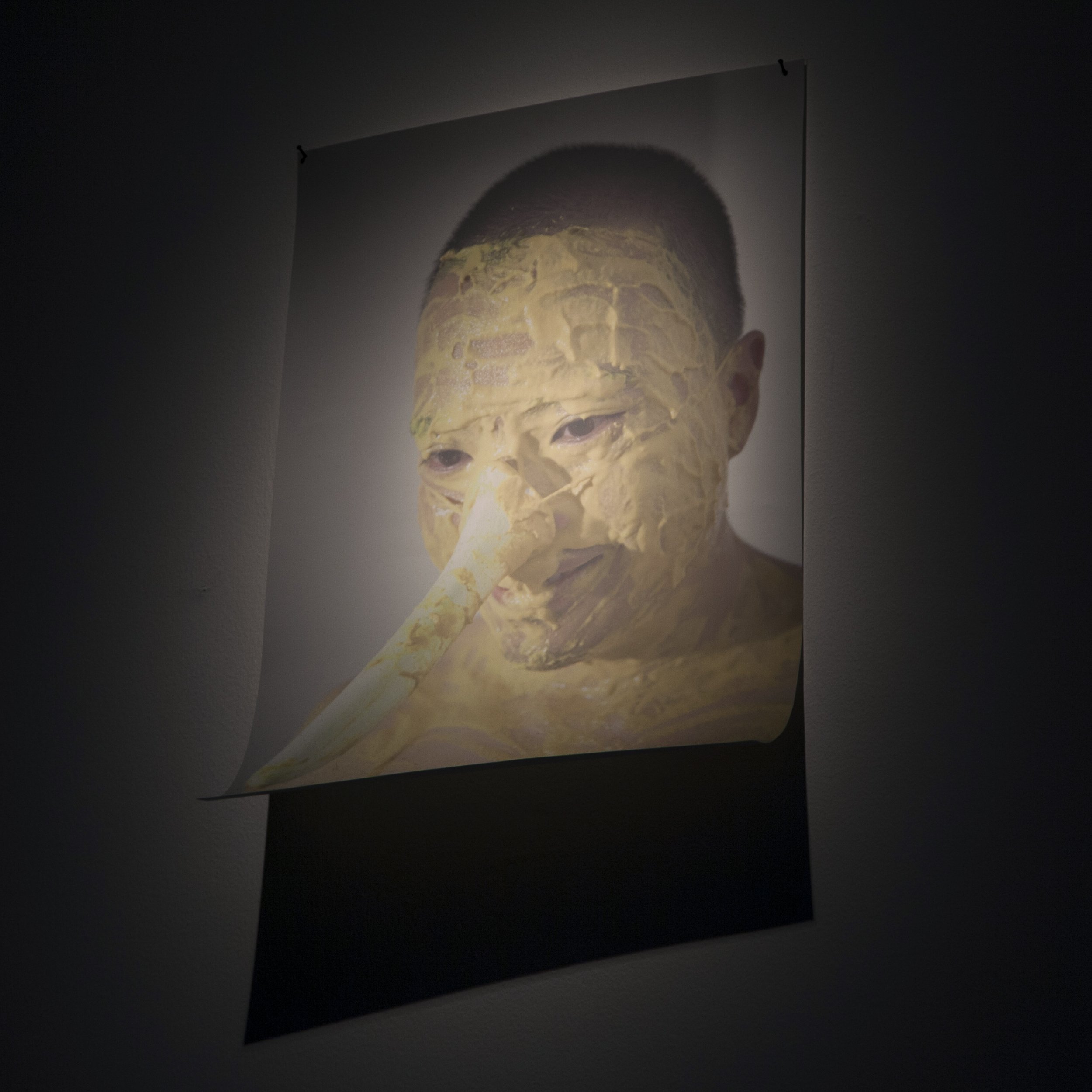

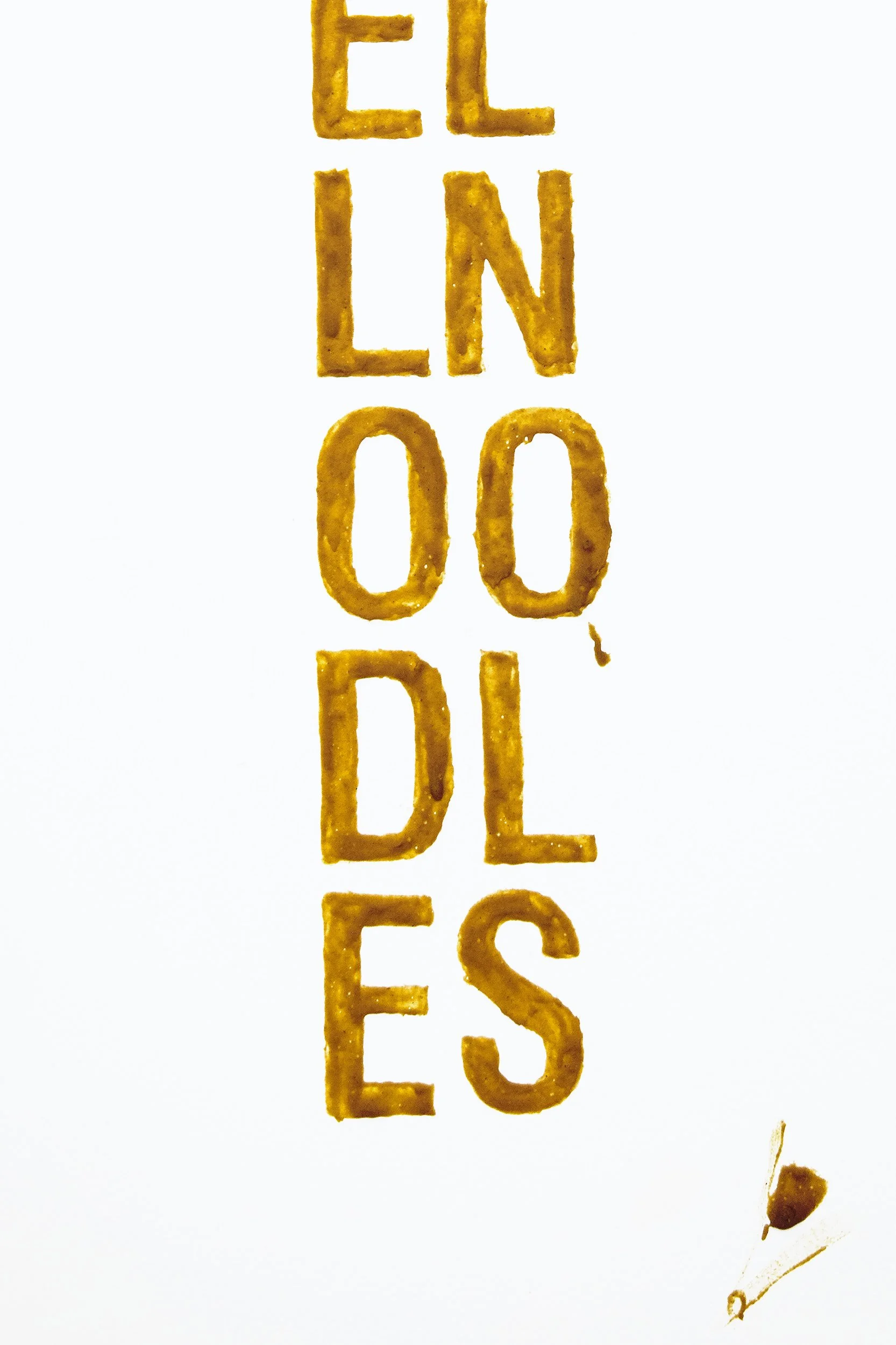

Questions of permanence, perfection, and desire comingle with conditions of temporal precarity, abjection, and the anxieties of meaning. White plaster, yogurt, eggshells, mustard, flesh, screens, neon signs, and educational texts both bring forth and disturb the processes and iconographies of classical art and ancient ritual, as well as the ingenious embracing of materiality key to many immigrant experiences. Throughout BOYSHOW, body, action, material, preparation, and study are presented in relation to social power dynamics, personal strategies of survival, and the spaces in between.

Installation view of Parinot Kunakornwong’s BOYSHOW at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (2019-2020)

Parinot Kunakornwong lives and works in Bangkok, Thailand. Working with many different media, his practice explores experiences of alienation through observations of everyday life, the momentary or transitory, and also inquiries into memory and history. His upbringing as third generation diaspora from China has been crucial for his practice.

His works are concerned with perceptions of the human body through a general method of appropriating objects and images that mediate cultural understandings of the body. The artist understands the body as formed through a complex interplay of inner and outer systems, and he disrupts this relationship to explore and provoke the suppressed and devalued. The range of references he employs includes autobiography, everyday objects and display, mass media, ritual, superstition, folk art, and art history.

-Brian Curtin

Kunakornwong has exhibited at Bridge Gallery (Bangkok, 2020); Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (Bangkok, 2019); Queer Arts Festival (London, 2018); NOVA | CONTEMPORARY (Bangkok, 2018); Tenderpixel (London, 2018); Cartel Artspace (Bangkok, 2017); TARS Gallery (Bangkok, 2016); Speedy Grandma (Bangkok, 2015); and The Invisible Dog Art Center (New York, 2012). He is a graduate of Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, and Goldsmiths, University of London, and attended Parsons School of Design in New York.

PARINOT KUNAKORNWONG Interviewed by BRIAN CURTIN

The title of your installation BOYSHOW at the large group exhibition Spectrosynthesis II-Exposure of Tolerance: LGBTQ in Southeast Asia at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre during 2019-20 referenced the infamous strip and sex shows of ago-go bars in Bangkok. Of course, you were not interested in an ethnographic engagement with this scene but, rather, the fetishizing of East Asian male bodies that is evident there and reflects any number of contexts; and by fetishizing, we usually mean infantilizing. What drew you to using your own body as proxy?

Partly it comes from personal experience and including harassment. I remember my first week in London and I was around Soho when some drunken guys approached and whispered into my ear if I sold noodles; or another time on the underground train, when it was jammed, a guy tried to touch my crotch. And I was assaulted by a white guy on a bus to Camberwell.

I think my body can be a pragmatic testing ground to explore power dynamics which have directed and conditioned my subconscious to do with affection or aversion towards something. This is essentially a question of desire to do with a perception of the “perfection” of white people that I gained from the depiction of white bodies on Christian artefacts; and also from Western art and media, or why certain types of bodies are represented as heroic and others as villainous.

But, of course, I don’t believe that what happens here is only a subjective feeling or entirely personal. It comes from a longer, social, history and hegemony that calculates to make one feel certain way. My body could be an example of many others who might share the same kind of body and experience I am talking about.

I think a large part of my condition and identity might be to do with the mixture between Chinese beliefs, Thai propaganda, Buddhism, Catholicism, and Western Pop culture. It’s interesting to figure out why I can’t relate to any of these local beliefs very deeply while I am familiar with the Western culture, but at the same time feel inferior and misapprehended. I think it’s hard to feel empowered under the standard that is set up by the West.

Detail: Forever Yogurt, 2017, 3.54 minutes, 2 channel video (one silent and one with audio), monitors, plaster, fridge, yogurt packages, mixing bowl

Detail: Forever Yogurt, 2017, 2 channel video (one silent and one with audio), monitors, plaster, fridge, yogurt packages, mixing bowl

Yes, Thailand is famed for its syncretistic beliefs and also the visibility of LGBTQ communities, which has led observers to believe that the nation is tolerant and accepting. Even local gay activists propagate the idea that the country is particularly tolerant, without noting that tolerance itself is a problem. The reality is very different: LGBTQ are relentlessly stereotyped in the media; the historic influence of Buddhism has bred a popular notion that queers are karmically damaged and in need of sympathy; and the current dictatorial government are blatantly co-opting a liberal agenda by aiming to introduce gay marriage. Your work On Condition (2019) in BOYSHOW is a means of revealing or exposing a deep-rooted homophobia and contradictions between belief systems.

You’re right. That notion about karma has traumatized me for years, and the Catholic school I attended made it even worse by injecting shame into it. Many of my parents’ generation don’t seem to understand that sexuality is not something I can choose. For On Condition, I researched on masculinity in the Thai military system and then I looked further into general education books at the National Library. I read mandatory general health texts for young students in different eras. I discovered that the books for students in the last decade are far more controlled than when I was a student, even though back then the teacher would blatantly rebuke the idea of being gay. The recent book constructs the role of students as a binary system and guides them towards notions of what life and family should be. In one section it clearly defined that a good person should act accordingly to one’s gender and respect nation, religion, and the king.

However I’ve been told that in recent years they have adjusted the curriculum for LGBTQ people. But it’s still very awkward as certain ideas are deeply embedded in the language and also tradition and very difficult for some conservative teachers to adjust. This curriculum reflects the system behind it, the public service, education department, and ideologies of what the country expects its people to be. It leads to the idea of what family, gender roles, life pursuit, and moral code should necessarily be.

On Condition Student Book, 2019

The objects you presented in the installation of BOYSHOW, which appear to be found, made and assembled, are mostly covered or made from white plaster. As we know, this is a highly coded material and colour in terms of perfection, purity etc. But you use plaster is a seemingly haphazard and, if I can say, ejaculatory way. Further, the all-white installation can seem ghostly or conjure ideas of memory. What was your intention with this material for this installation?

Plaster is such a traditional art material, used in history for very long time and especially in classical art. In the past it was used for preparation or study before making a more permanent artwork. Plaster also has a quality that is very different before and after it’s cured, the latter almost like a frozen form of liquid skin and time. You know, it was also used in excavation sites like Pompeii or to make death masks or other objects in ancient ritual. I feel that parts of my skin, body, and action seep into the material during the ritual or process of making my work. These qualities and a sense of embedded history are quite close to what I essentially want to say.

Mr. Cloud, 2019, neon light

Many of your installations have a “messy,” precarious and temporary quality. You also appropriate found objects and materials (including mustard!). Without seeking to define a “queer aesthetic,” these methods nevertheless have been common among female, POC, and queer artists. What attracted you to employing these methods?

I think it’s the nature of how my brain and body work, that I can’t define anything clearly as one way to communicate. For me, “queer aesthetics” can be quite limited and categorize what a person or matters is or are. I’m interested more in shifting meanings to do with context. Perhaps this interest emerges from being a kind of migrant that has to learn to embrace everything and try to arrange in a way that makes sense to me. And I like a sense of urgency when things are created, which is perhaps the sense shared among people in Southeast Asia. The temporary quality to me feels quite alive insofar as it has life span only for the period of the exhibition when people can interact with it.

You grew up in Bangkok and studied in New York and then London. Currently based in Bangkok, how was your experience of these other cities or countries as an artist?

They helped me a lot in unpacking misconceptions I had about art media and education. One interesting aspect I discovered was that hierarchies don’t really work the same way in other countries, for example, the class system in the UK is very strong. In Thailand, hierarchies are dictated much by language and ritual around how one should acknowledge one’s position in society. Another experience was how I was treated so differently, on many occasions as inferior in the West. I believe popular media and historical understandings must be limited. Being Thai automatically categorizes me as working in the sex industry, or being unintelligent, or incompetent. I remember one English guy I talked to at the ICA in London told me he had no clue as to why some foreigners can’t pronounce the same way the English do. I’ve experienced street harassment and racism many times, as I discussed, and even within academic institutions that otherwise seem to support LGBTQ or feminism. I also remember some people rejecting discussions about spirituality.

How is the art scene in Thailand for emergent artists such as you? We are aware of an increase in spaces and opportunities locally and regionally, but I feel that Berlin, London and New York remain the destinations of choice. Do you think that Asian cities can ever seriously compete internationally?

There’s no freedom of speech here now. We live under a dictatorship. A lot of what we do has to be self-censored. A climate of fear, angst, and anxiety has permeated around the country. In Thailand there was a glimpse of hope sporadically during the elections and a bit after the recent protests, but this has abruptly disappeared. Before the C-19 pandemic I hoped the local scene and region would grow and become something. Suddenly everything stopped and now it’s very hard to talk and to think about a growing art scene that never had enough infrastructures to keep going anyway. I honestly can’t be optimistic about it as most Asian countries remain politically still with some form of regime from the legacy of colonialism. I now wonder about what kind of art could be supported and emerge from such scenarios and what kind of social engagements can be performed?

THE COMPLETE BOYSHOW IMAGE CATALOGUE

Brian Curtin is an Irish-born art critic based in Bangkok and the author of ‘Essential Desires: Contemporary Art in Thailand’ (Reaktion Books, 2021). He lectures in the Department of Communication Design at Chulalongkorn University. www.brianacurtin.com

Essential Desires: Contemporary Art in Thailand

Brian Curtin

Essential Desires: Contemporary Art in Thailand is the first major, fully illustrated survey of Thai art in thirty years. Brian Curtin shows how Thai artists negotiated their emergence on the global art stage while dealing with pan-Asian regionalism and nationalism at home.

This book traces the influences on contemporary Thai artists, from the impact of consumerism in Bangkok in the 1990s to the legacies of tradition, and their relationship to the nation’s often-volatile political stage. Curtin, in his exploration of Thailand’s fascinating art scene, shows how Thai artists are generating new ideas about their country.

258 × 197 × 19 mm •176 pages • Hardback•105 colour illustrations

Townsend extends special thanks to Brian Curtin for his generosity and contributions to Townsend’s presentation of BOYSHOW. Images throughout courtesy of the artist and the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre.